Is federalism the cause of our national ills?

In two opinion essays for Governing, Stephen Legomsky, a law professor emeritus at Washington University and author of “Reimagining the American Union,” argues that many of the nation’s political problems are a direct result of federalism. The root of those problems, he contends, lies with the states. Yet a closer reading of his essays suggests the issue runs much deeper than federalism itself. His argument continues the progressive movement’s long campaign to fundamentally alter American constitutionalism.

“Many political problems, whether enduring ones such as the Electoral College, the structure of the U.S. Senate, gerrymandering and voter suppression, or more recent ones such as state pre-emption of municipal functions, are rooted in our federal system. Too often, states are the chief culprit,” wrote Legomsky.

Legomsky argues that “the U.S. states, through their outsized roles and cynical actions, have grotesquely distorted electoral outcomes and done massive damage to democracy in the process.”

He proposes what he calls “a radical solution: abolish the states.” His alternative would replace federalism with a unitary system of government, though it would still allow local governments to exist. As Legomsky argues:

Under my proposed restructuring, some current state functions would be reassigned to the national government, such as election administration and professional licenses. The lion’s share would devolve to cities and towns. Their elected leaders are not just geographically closer — and therefore more accessible — to the people they represent. They are also far more likely to share their constituents’ values, and to be motivated to serve their interests, than a state legislature can ever be.

Further he asks:

Do I really want three separate governments — national, state and local — all taxing me and regulating me? Wouldn’t two do just fine? And which politicians do I trust more — state legislators or my neighbors on the city or town council? Finally, do I really want to keep paying the costs of maintaining 50 separate state legislatures and 50 state bureaucracies? What has that gotten me?

Legomsky acknowledges that his proposal is “merely a thought experiment, because there is obviously no prospect of the states going away any time soon.” But his argument is more than an abstract exercise.

Blaming states for the nation’s political ills goes deeper than a critique of federalism. It reflects a broader progressive and modern liberal impulse — not only to alter the Constitution, but to reject its underlying principles as outdated or failed.

The arguments in Legomsky’s essays not only discredit the states, but also amount to a call for abolishing both the Electoral College and the U.S. Senate. Institutions that progressives often view as anti-democratic.

These arguments trace their roots to the Progressive movement. In the early 20th century, Progressive intellectuals, politicians and legal theorists began challenging the idea that the Constitution’s principles had endured. They criticized doctrines such as the separation of powers and argued that a government of limited authority could not adequately govern a modern, industrial society that to them was growing increasingly complex.

“Liberals have for many decades tried to replace the Constitution’s ideas of limited federal and presidential power, checks and balances, and federalism with majoritarian democracy, expanded and centralized government, and strong presidential leadership,” said Claes G. Ryn, a professor emeritus of politics at Catholic University.

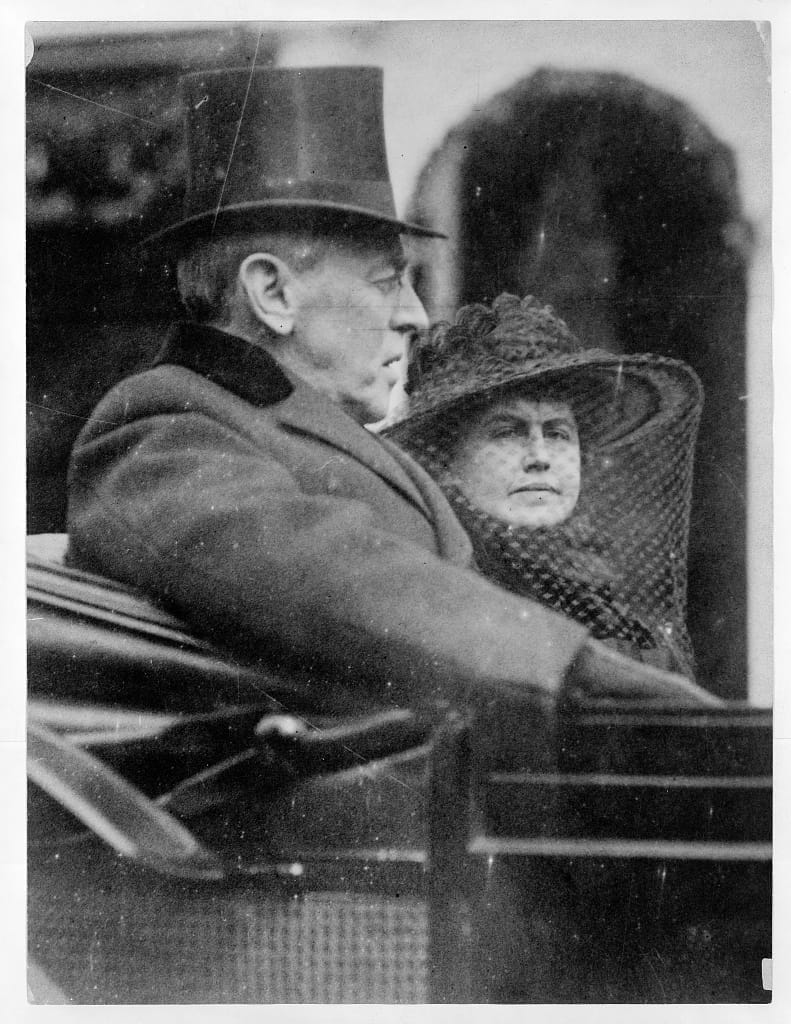

Progressives saw the Constitution as a “living” or Darwinian document that should evolve with the times. President Woodrow Wilson, a political scientist before entering elected office, was among its chief critics.

Wilson argued that “our life has broken away from the past” and that “the old political formulas do not fit the present problems; they read like documents taken out of a forgotten age.” He contended that the nation was “in the presence of a new organization of society.”

To address the political and economic challenges of their time, Progressives argued that the federal government needed to assume greater authority, particularly through regulation. Leaders such as President Theodore Roosevelt maintained that an energetic national government was essential and that constitutional limits on federal power should not obstruct progressive reform.

The foundation of the modern administrative state, the federal bureaucracy, emerged from the Progressive movement. By combining a powerful executive with a growing web of agencies, Progressives believed they could better advance reform.

“A dislike for the constitutional republicanism of the Framers has been integral to modern American liberalism,” said Claes G. Ryn. “Liberals have long sought an imperial presidency and a corresponding centralization of government.”

The rise of the administrative state marked the centralization of federal power and “represents the very consolidation of power opposed by all of the Founders — Federalist as well as Anti-Federalist.”

The most significant transformation came under President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who in 1932 declared that “the day of enlightened administration has come.” His New Deal solidified the progressive vision of a “living” Constitution.

Echoing Wilson, Roosevelt argued that “the task of statesmanship has always been the redefinition of these rights in terms of a changing and growing social order.” He added, “New conditions impose new requirements upon government and those who conduct government.”

FDR’s New Deal was transformational not only for American government but for the Constitution itself, resulting in a de facto constitutional revolution that reshaped the nation’s political culture.

The late Judge Robert Bork described the New Deal as an “economic and governmental upheaval.” He wrote that it “brought about a sudden and enormous centralization of power in Washington over matters previously left to state governments or left in private hands — a centralization accomplished largely through the assumption of greatly expanded congressional powers to regulate commerce and lay taxes.”

Franklin D. Roosevelt’s presidency energized the federal government, expanding its reach far beyond constitutionally defined limits.

Progressive and liberal intellectuals, as Claes G. Ryn observed, have long admired FDR and continue to view his administration as a model for “evolving” constitutional change. Ryn pointed to political scientist and Roosevelt biographer James MacGregor Burns, who was sharply critical of the American Founding.

“Burns idolized FDR, and he sharply criticized the U.S. Constitution, whose ‘Madisonian’ checks and balances blocked the progressive policies that he believed the American people wanted,” wrote Ryn.

Whether it is Burns, Legomsky, or other academics, the criticisms of the Constitution are similar, and so is the refrain for more democracy. Burns, just like Legomsky, favored the elimination of the Electoral College.

Legomsky’s call for a unitary system of government, with local governments operating beneath it, reflects the reality of today’s federal landscape. The centralization of the federal government has already turned many states into little more than administrative districts dependent on federal funding.

Progressives have succeeded in centralizing authority in Washington. Their push to abolish the Electoral College and question the legitimacy of the Senate reflects a continued effort to weaken constitutional federalism. Yet both institutions remain essential safeguards against the consolidation of power.

“Federalism is in the bones of our nation, and abolishing the Electoral College would point toward doing away with the entire federal system,” said historian Allen Guelzo.

The term “democracy” is frequently misused, and as civic education erodes, many Americans fail to grasp that the Founders rejected pure democracy.

“The Electoral College was designed by the framers deliberately, like the rest of the Constitution, to counteract the worst human impulses and protect the nation from the dangers inherent in democracy,” said Guelzo.

Americans must understand that federalism is vital to the constitutional republic. It is as essential as the separation of powers and checks and balances. “The framers wove federalism into the constitutional fabric,” wrote the late scholar James McClellan.

Both the Electoral College and the Senate ensure that states have a voice and citizens retain equal representation. The Senate was designed to give each state equal representation, balancing the House of Representatives, which favors larger states through population-based membership. Before the 17th Amendment, state legislatures elected senators, providing an additional check on federal power.

Abolishing the Electoral College or transforming it into a direct national vote might appear more “democratic,” but it would diminish the influence of smaller states such as Iowa. The same would occur if the Senate’s structure were altered. These safeguards ensure that small states continue to have a meaningful voice in national politics.

Federalism is more than just dollars flowing from the federal government to state and local governments. It is something far greater, that is, a constitutional pillar. “Yet there is no more misunderstood principle associated with American government and politics than federalism,” writes Eugene Hickock in “Why States? The Challenge of Federalism.”

Hickok explained that federalism “is about deciding what should go between Washington and the states; it is about the nature of the relationship between Washington and the states.” As a constitutional principle, he added, it defines “the delineation of authority between the national government and the states, and speaks to the overarching concept of limited government and the preservation of individual liberty.”

Since the New Deal, progressives have succeeded in expanding centralized power, while both major parties have embraced stronger executive authority. Compounding the problem, civic education has deteriorated. How can Americans defend federalism or the Electoral College if they no longer understand them?

Preserving federalism will require more than electing constitutionalists or appointing originalist judges. As Ryn observed:

Many defenders of the old American Constitution seem to think that all that would be needed to save the Constitution would be to persuade Americans of the correct interpretation of the framers’ intent. These constitutionalists live in a world of abstractions, a dreamworld of their own. … There is only one way to revive American constitutionalism, and that is for Americans — from leaders to people in general — to revive or freshly create something like the older type of morality and to start living very differently. Should that not be a likely development, the future of American constitutionalism is bleak.

That renewal, as Ryn suggests, depends on more than policy. It requires a citizenry recommitted to the moral and civic virtues the Founders saw as the foundation of liberty.

John Hendrickson is policy director at Iowans for Tax Relief.