Local news is work that must be done. But by whom?

Roger Scruton is loved among conservatives for his political and philosophical work, where he covered topics like localism, beauty, national identity, architecture, and tradition. I enjoyed his “How to be a Conservative” as a more approachable primer on the subject than Russell Kirk’s “The Conservative Mind.”

Scruton was also a journalist by trade, providing commentary on the latest in British and European politics, economics, and culture from his conservative perch. He was even the founder of a popular right-of-center newspaper called The Salisbury Review.

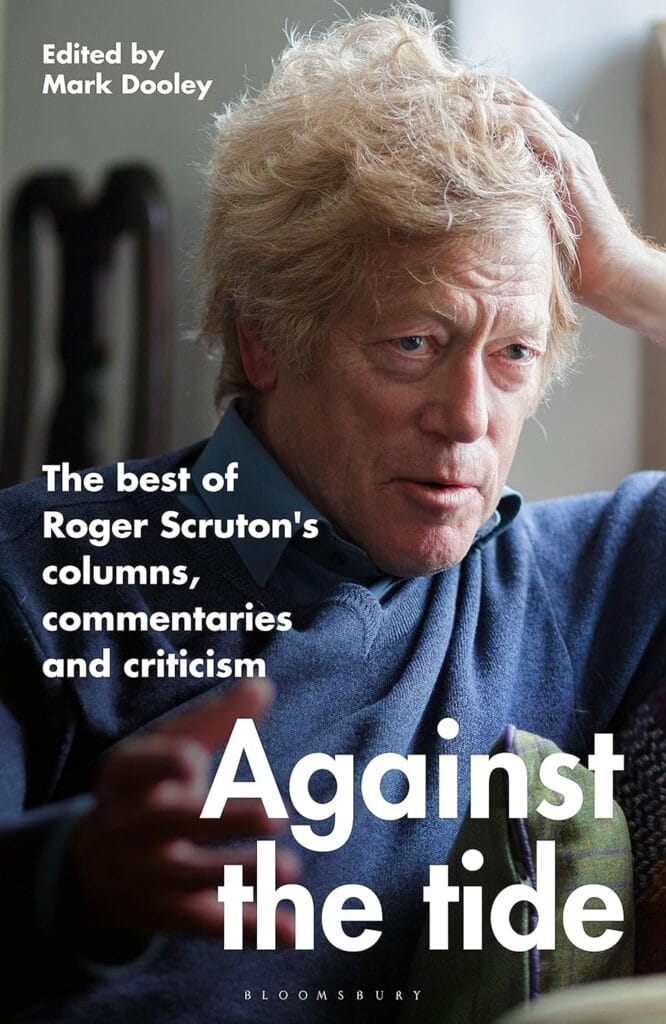

Scruton’s columns, in contrast to his more abstract philosophical work, were more particular to time and place. This particularity makes it somewhat more difficult for those outside that context, like an American in 2024, to pick up and casually read. But as I was reading through a collection of his columns titled, “Against the Tide,” comments in the introduction by the book’s editor, Mark Dooley, struck me as important to my work and to that of journalists more broadly.

Dooley told Scruton that he had stopped writing for the Irish Daily Mail and could finally enjoy “writing about philosophical and spiritual matters again.” Scruton agreed that Dooley was fortunate, then added in defense of journalism, “but writing about the issues that confront us is the work that must be done.”

Scruton’s book “News from Somewhere” considered the importance of belonging somewhere in particular, in his case a rural English farm. He argued that one’s life can reach new depths when planted in place — whether that place is rural or urban — rather than pulling up your shallow roots every few years. Part of making people care enough to stick around is having information available to those in the community. And making people care about their surroundings is often key to making them thrive. Research shows that not only does voter participation plummet when a local newsroom shutters, but people even stop running for local offices.

It’s not always exciting work for local journalists to go to the city council meetings, community theater performances, high school sports games, or the ribbon cutting for the new dentist’s office. But not doing it means important stories that bind people together don’t get told. It also might mean that corruption by local politicians goes unnoticed or that taxes are raised, and nobody has a chance to put in their two cents before they’re forced to put in three.

Increasingly, though, the work is being left undone. Northwest University’s Medill Local News Initiative tracks the health of local news coverage in the United States, and their 2023 report was dire.

“Of the 3,143 counties in the U.S., more than half, or 1,766, have either no local news source or only one remaining outlet, typically a weekly newspaper,” the report stated. “The loss of local newspapers ticked higher in 2023 to an average of 2.5 per week, up from two per week last year… Since 2005, the U.S. has lost nearly 2,900 newspapers. The nation is on pace to lose one-third of all its newspapers by the end of next year. There are about 6,000 newspapers remaining, the vast majority of which are weeklies… The country has lost almost two-thirds of its newspaper journalists, or 43,000, during that same time.”

At the risk of oversimplification, we can largely lay this crisis at the feet of the internet, if it had any. At one level, the internet is at fault due to “creative destruction” of an outdated model. It is vastly more efficient at disseminating information than a pile of paper that has to be printed on and then delivered. This efficiency is an economic positive.

But if it was only about a more efficient delivery mechanism, then those same local publishers should have just made the switch to websites and social media and then pocketed the savings on ink and paper. They largely have made the switch, but it hasn’t stopped their bleeding.

This brings us to a second reason the internet is at fault. In Scruton’s essay, “Hiding Behind the Screen,” he points to a less positive effect of the internet — voluntary isolation, or what some have called “atomization.”

“There is a novel ease with which people can make contact with each other through the screen,” said Scruton. “No more need to get up from your desk and make the journey to your friend’s house. No more need for weekly meetings, or the circle of friends in the downtown restaurant or bar. All those effortful ways of making contact can be dispensed with: a touch of the keyboard and you are there, where you wanted to be, on the site that defines your friends.”

Lest you think his war against screens only targeted the internet, here’s what he had to say about television in the same essay, “The television has, for a vast number of our fellow human beings, destroyed family meals, home cooking, hobbies, homework, study, and family games. It has rendered many people largely inarticulate, and deprived them of the simple ways of making direct conversational contact with their fellows.”

What he’s arguing for is the real human particularity of existing somewhere in time and place. If local news is work that must be done, there must be people who care enough to read it. If they live their lives hiding behind a screen and interacting on a national or international scale, their local-scale life becomes largely irrelevant.

News consumers seem to be telling local news producers that the war in the Middle East, the crisis at the border, the celebrity awards show, or the pro basketball team from a city you used to live near, are all infinitely more important than local conflicts, crises, celebrities, or sports. Is it up to local publishers to convince them otherwise?

There was a similar time of great upheaval in the American news business in the mid-1800s, the “penny press period,” that may give some insight into how future publishers might get the masses to consume what they publish. Dwight Teeter, journalism professor at University of Tennessee, has a succinct but informative book about the penny press period, “The Devil and His Due: James Gordon Bennett, the Penny Press, and the Rise of Modern Communications,” which was also the only book I could find on the topic.

Before that time, the political parties dominated the newspaper industry. The papers were largely harnessed to deliver heavily biased messaging to convince politically active, well-educated elites. The average cost of a paper was about 6 cents, which was the cost of “a good dinner or a pint of whiskey,” so following the news was a privilege of the wealthy.

But then, long story short, a few entrepreneurs in New York City decided to offer daily news for a penny in a completely new format. They targeted, instead of wealthy partisans, the common man in the street. Because of this, they mostly cut ties with political parties (with the notable exception of Horace Greeley and his Tribune) and instead took a non-partisan angle, often refusing to cover politics at all. Instead, they hired the first “reporters,” who would cover salacious and entertaining stories in the area — crime, sports, theater, gossip, even completely made-up “tabloid” stories about bat-people living on the moon (a real article by the Sun now called the 1835 “Moon Hoax”).

A decade later, the telegraph hit and changed everything again. For the first time, news could be delivered almost instantaneously (using the painfully slow, to modern standards, Morse Code). These New York City penny press rivals (who had at times literally beat each other with canes in the street) immediately jumped into action and created “The New York Associated Press” to take advantage of the new technology and monopolize the “wire,” as it was called. Local news publishers everywhere subscribed to the AP Wire to get stories from around the world instantaneously, and to contribute their own.

Almost 200 years later, they still do. This period of the penny press and the telegraph defined the modern news business and journalism, giving us defining innovations like reporters, subscription news wires, crime and sports beats, and (allegedly) objective political coverage.

Now we are in another destructive and disruptive era for media. Local news publishers, just like the 6-cent partisan press, have had their model smashed to bits. The smoke has not cleared yet enough to let us see what will emerge on the other side.

Will it be independent journalists and small-scale entrepreneurs serving niche audiences? Will non-profit advocacy journalism replace the for-profit model, since there isn’t much profit to be made? Could one version of advocacy press even be the return to a “party press,” where local political activists cover the city council meetings nobody else will, even if just in post-meeting social media rants?

All these things are happening, but none are currently sufficient to cover all the beats once covered by the local newspaper. Some even want the federal government to outright pay for local news. Anyone who has seen the BBC in Britain or CBC in Canada knows that’s a bad idea. The same author’s suggestion of offering tax breaks to news outlets, regardless of leaning, is a bit more palatable, but still problematic.

Like Scruton, I believe local news coverage is work that must be done. An informed citizenry being vital to maintaining our republic, hopefully, consumers and journalists will arrive together at a model so it can thrive again.

David Larson is opinion editor at Carolina Journal.