Fountains of wisdom: 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence is a chance for national renewal

July 4, 2026, will mark the 250th birthday of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Many events, articles, books, and programs are in the works to commemorate this important anniversary, but the crucial challenge will be whether or not these events will rekindle a new spirit of appreciation for the principles of the American Founding.

“If you ask me what the greatest danger America faces today, it’s itself,” stated Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court Neil Gorsuch in a recent interview on Fox News. Justice Gorsuch referred to both the divisions in society and the decline of civic education. The trend is not new, but it remains alarming how increasingly Americans do not know the basics of their history, but also the foundation of our government meaning the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution.

This was not always the case. For conservatives within the Republican Party during the 1920s, the Constitution was the foundation of the American system. These Republicans or “Old Right” conservatives believed that the Constitution limited the powers of government and protected liberty. It has been described that “a veritable cult of Constitution worship” was attributed to many conservatives during this era. Presidents Warren G. Harding, Calvin Coolidge, and Herbert Hoover were just three that held sacred the principles of the American Founding.

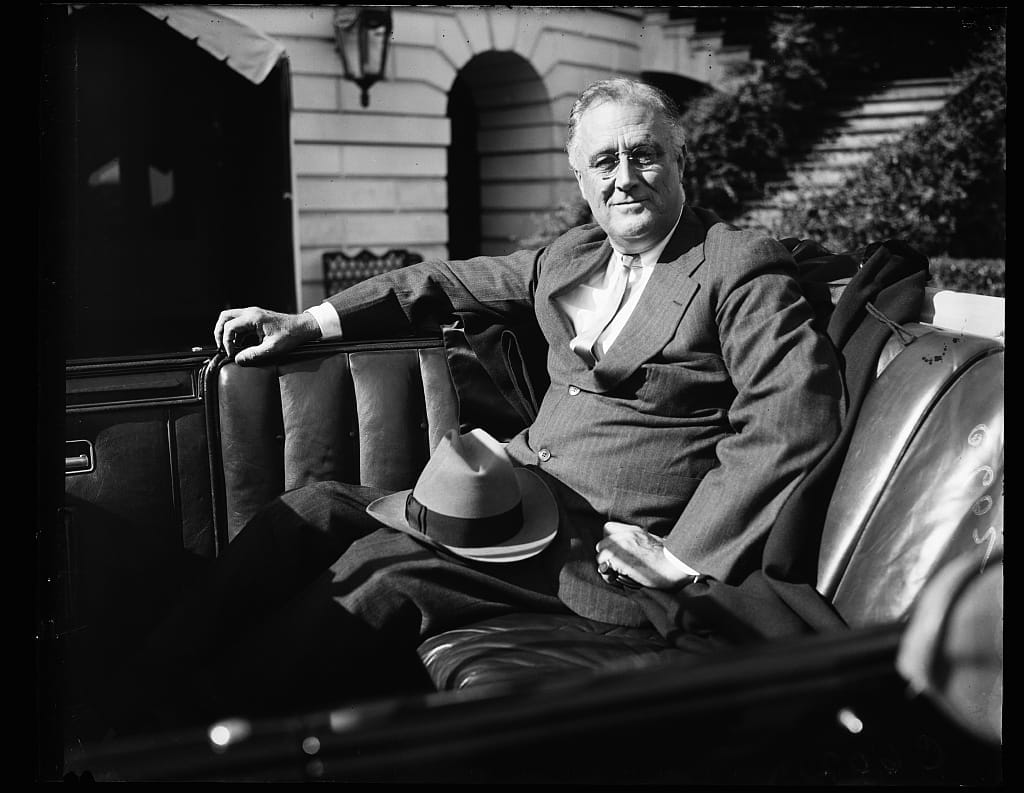

For some, Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover will be viewed as irrelevant, but it is often forgotten that they and other conservatives during their era defended the principles of the American Founding against the political forces of progressivism. Progressives such as Presidents Woodrow Wilson and Franklin D. Roosevelt advocated for major constitutional changes.

In reference to the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, both Wilson and Roosevelt argued that modern, industrial, “mechanical” society cannot be beholden to principles of the American Founding, which in Wilson’s view were substantially flawed. “The old political formulas do not fit the present problems; they read now like documents taken out of a forgotten age,” wrote President Wilson. During the 1932 presidential campaign, then-New York Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt argued that “the task of statesmanship has always been the redefinition of these rights in terms of a changing and growing social order.” “New conditions impose new requirements upon government and those who conduct government,” stated Roosevelt.

Unlike the Progressives, Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover rejected the “living” Constitution. Further, they understood that the principles of the American Founding were based on foundational truths. In reflection upon the Declaration of Independence, Coolidge stated that “it was conservative and represented the action of the colonists to maintain their constitutional rights which from time immemorial had been guaranteed to them under the law of the land.”

Coolidge argued what made the Declaration unique in human history were three crucial principles, including “the doctrine that all men are created equal, that they are endowed with certain inalienable rights, and that therefore the source of the just powers of government must be derived from the consent of the governed.”

The Declaration of Independence, Harding argued, “was the bold, clear statement of human rights by an association of fearless men who knew they were speaking for liberty.” Further, Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover understood that the principles of the American Founding were not new creations.

Coolidge noted that “these principles were not altogether new in political action,” and Hoover argued that “step by step they had been secured through the Magna Carta, the growth of common law, the ‘Petition of Rights,’ and the Declaration of Rights, until they reached full flower in the new republic.”

It was not just political theory and the English constitution that influenced the Declaration, but Coolidge acknowledged the influence of Christian theology. He referenced the Reverend Thomas Hooker who in a sermon stated that “the foundation of authority is laid in the free consent of the people…and the choice of public magistrates belongs unto the people by God’s own allowance.”

In addition, Coolidge argued that “when we take all these circumstances into consideration, it is but natural that the first paragraph of the Declaration of Independence should open with a reference to Nature’s God and should close in the final paragraphs with an appeal to the Supreme Judge of the world and an assertion of a firm reliance on Divine Providence.”

“No one can examine this record and escape the conclusion that in the great outline of its principles the Declaration was the result of the religious teachings of the preceding period,” stated Coolidge in specifically referencing the theology of Jonathan Edwards and George Whitefield whose thought and preaching “stirred the people of the colonies in preparation for this great event.”

Finally, for Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover the Declaration was not just an isolated document, but it contributed directly to the Constitution. “It was in the contemplation of these truths that the fathers made their declaration and adopted their Constitution,” argued Coolidge.

President Harding called the Constitution the “ark of the covenant of American liberty,” reminding his fellow citizens that “it is good to meet and drink at the fountains of wisdom inherited from the founding fathers of the republic.” For Harding, the Constitution was sacred: “Let no one proclaim the Constitution unresponsive to the conscience of the republic.”

Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover rejected the idea that the Constitution was outdated. Harding argued that “certain fundamentals are unchangeable and everlasting.” “About the Declaration there is a finality that is exceedingly restful,” argued Coolidge. This was in contrast to the Progressive philosophy. As Coolidge famously stated:

It is often asserted that the world has made a great deal of progress since 1776, that we have had new thoughts and new experiences which have given us a great advance over the people of that day, and that we may therefore very well discard their conclusions for something more modern. But that reasoning cannot be applied to this great charter. If all men are created equal, that is final. If they are endowed with inalienable rights, that is final. If governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed, that is final. No advance, no progress can be made beyond these propositions. If anyone wishes to deny their truth or their soundness, the only direction in which he can proceed historically is not forward, but backward toward the time when there was no equality, no rights of the individual, no rule of the people. Those who wish to proceed in that direction cannot lay claim to progress. They are reactionary. Their ideas are not more modern, but more ancient, than those of the Revolutionary fathers.

Hoover warned about the consequences of those who “have in despair surrendered their freedom for false promises of security and glory.” The principles were moral, and Hoover argued that “neither would sacrifice of these rights add to economic efficiency nor would it gain in economic security nor find a single job nor give a single assurance in old age.”

“Men oftentimes sneer nowadays like it were some useless relic of the formative period…Others pronounce it time-worn and antiquated and unsuited to modern liberty…,” stated Harding. This was the opinion of President Roosevelt in 1944 when he called for a “Second Bill of Rights.”

“This Republic had its beginning, and grew to its present strength, under the protection of certain inalienable political rights—among them the right of free speech, free press, free worship, trial by jury, freedom from unreasonable searches and seizures. They were our rights to life and liberty,” stated President Roosevelt. Further, Roosevelt argued that “as our Nation has grown in size and stature, however—as our industrial economy expanded—these political rights proved inadequate to assure us equality in the pursuit of happiness.”

President Roosevelt argued “that true individual freedom cannot exist without economic security and independence,” and therefore the federal government had a responsibility to provide economic security. “In our day, these economic truths have become accepted as self-evident. We have accepted, so to speak, a second Bill of Rights under which a new basis of security and prosperity can be established for all regardless of station, race, or creed,” stated President Roosevelt in justifying his “evolving” rights under the Constitution. The new “rights” included a useful job, education, medical care, home ownership, enough income to provide food and clothing, among other elements of economic security.

It is not that Harding, Coolidge, or Hoover opposed reform or were even libertarian in their philosophy. They believed that the principles of the Constitution limited government and that the federal government could not just undertake any policy “emergency,” nor were they arrogant enough to believe they could create new constitutional rights.

Harding emphasized that the Constitution limited the power of the federal government and reserved “to the people in the states and their political subdivisions control of their local affairs.” In short, Harding was underscoring the importance of federalism. Roosevelt’s “Second Bill of Rights” were all policy issues that were the jurisdiction of states and localities. “Ours, as you know, is a government of limited powers,” stated Coolidge.

Harding described the Constitution as an “anchor,” but he stated that “it cannot be held a rigid, immovable thing…” The Framers had established a process for amending the Constitution and Harding used the Bill of Rights as an example. Although viewing the Constitution as a “document of conservative self-restraint,” Harding, just as with Coolidge and Hoover, believed in the principle of prudence. Hoover described this principle when he stated:

“My idea of a conservative is one who desires to retain the wisdom and experience of the past and who is prepared to apply the best of that wisdom and experience to meet the changes which are inevitable in every new generation.”

Today, we can learn much from the wisdom of conservatives such as Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover. In our culture, politics, and policy the nation needs to reembrace the principles of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution.

The 250th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence is a chance for cultural renewal. Harding called for “a new baptism of constitutionalism in the republic,” and he stated that the “Constitution is the rock on which we build; it is the foundation on which this republic will endure.” “We have the duty to preserve the inherited covenant of the fathers; we have the obligation to hand onto succeeding generations the very republic which we inherited,” stated Harding.

Harding warned the nation to be ever watchful of constitutional drift—a warning that is applicable to today. “I wonder what the great [George] Washington would utter…if he could know the drift today, stated Harding.” A question worth considering ourselves.

In reference to the Founders Coolidge stated, “we do need a better understanding and comprehension of them and a better knowledge of the foundations of government in general.” In addition, Coolidge noted that “we must go back and review the course which they followed.”

It is time to return to the fountains of wisdom of the American Founding and “review the course which they followed.”

John Hendrickson is policy director at Iowans for Tax Relief.