Existing to help people: An interview with Michael Reitz

Michael Reitz is the executive vice president of the Mackinac Center in Midland, Michigan. His focus is to turn the organization’s free-market recommendations into reality. Reitz, an attorney, oversees policy development, communications, fundraising, and the Center’s strategic plan. In 2021, the State Policy Network recognized Reitz with its Overton Award for his work across the network. He recently spoke with American Habits senior editor Ray Nothstine.

Mackinac is a model organization for influencing public opinion. How has your media arm, Michigan Capital Confidential, helped the taxpayers of your state and better positioned Mackinac to communicate many of its ideas to the public?

Reitz: Michigan Capital Confidential is impact journalism. It’s journalism that tells stories for a purpose. It ties to our mission statement. We enhance the quality of life in Michigan by doing three things: developing free market policies, challenging government overreach, and fostering a climate of public opinion that encourages policymakers to act in the public interest.

That last one, fostering a climate of public opinion, is impossible without the work of our journalism arm. We find stories of people who have been harmed by government policy, we tell those stories, and we follow up. We seek justice through the legislature and through the courts, but also through the storytelling process.

What are a few policy areas in which Mackinac has made the biggest impact in Michigan—or even nationally—in the last few years?

Reitz: We have many stories. One is pension reform. We knew that we needed to reform school pensions in Michigan. The challenge is it’s not a particularly exciting issue for the average taxpayer and it’s got very low salience. Most people don’t really understand how a broken government pension system could affect them.

When we took the issue on, we worked with State Policy Network. Together we did message testing and ran focus groups to learn if the issue resonates with people who are not that tuned into what’s going on in Lansing or Washington, DC. We discovered that people do care about this issue if they understand the connection to their everyday lives.

We had the example of the Detroit bankruptcy to point to. We could say, look, when a city or a municipality or a county or a state doesn’t manage its financial obligations well, it’s going to affect all the services that government should provide. When we made that connection for people, it really made a difference in whether they cared about that issue.

We found a couple of retired teachers who talked about this issue of pension security. We recorded a video of them telling their story and pushed that out to thousands of people all around the state who heard it and responded to it, which made a difference in getting that legislation across the finish line.

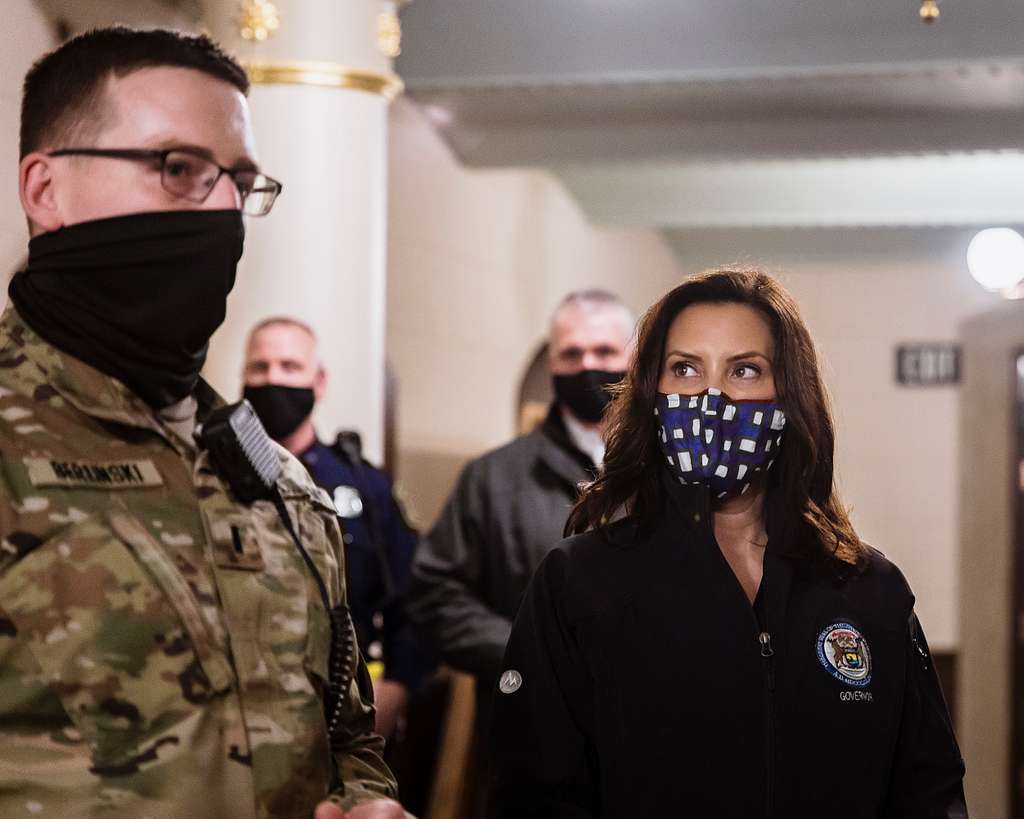

One other example was COVID-19. If you remember those early days in 2020, people just weren’t sure what was going to happen: Is this a really serious threat? How deadly is it? How contagious is it? We thought it made a lot of sense for the state to take some precautionary measures in the first few weeks. We even applauded Gov. Gretchen Whitmer on some of her early moves to contain the spread.

Very quickly, it became apparent that Gov. Whitmer was using the crisis to expand her power. She told the Legislature not to return to Lansing, saying she had the situation under control. She didn’t need them to come back to Lansing to address the pandemic and the lockdowns. That was a problem. It didn’t inspire confidence with the people and failed to acknowledge the role of multiple branches of government.

Gov. Whitmer’s actions also violated state law. In Michigan a governor can initiate an emergency, but the Legislature has a say in how long it lasts. No governor can declare an endless emergency without some checks and balances. Our legal team began looking for a compelling case to bring against the governor.

We were able to find doctors and several medical centers whose ability to provide services was substantially affected because of the lockdowns.

The governor’s orders affected the quality of life for clients and patients—their mental health, access to care. One client’s patient had to postpone a surgery and developed gangrene. Another was denied an important surgery to repair a damaged feeding tube. Our clients were incredibly courageous in those uncertain days.

The lawsuit against Gov. Whitmer went to the Michigan Supreme Court. We won unanimously on the question of whether the governor could initiate an endless emergency. We were then able to see power distributed to agencies and to the Legislature in terms of the decision-making on how to manage that crisis.

This win got a lot of public attention. That’s not always a common occurrence at think tanks. We had people coming up to us, in social settings and on the streets, saying, “Hey, great work. That was awesome what you did.” It was gratifying to see that reaction from people who knew the significance of the win our clients won at the state Supreme Court.

Tribalism is all the rage in American politics today. What is your thought on divided government? Because there’s been some real opportunities for reform. Do you find this true at Mackinac? There are several states we can point to right now where there’s been some advantage to divided government. Do you feel like that can be true for an organization like yours and just maybe even broadly more for the residents and the people that live within that state?

Reitz: I think you’re right. Partisanship exists at every level of government. Certainly, you see it in Washington, DC, and there seems to be an erosion of the value of bipartisan collaboration. It used to be that you’d win points for working in a bipartisan fashion. For whatever reason, today the opposite is true: You win points if you don’t work with the other side.

That thinking exists at the state level as well—or it can.

We’ve worked hard to identify areas where we can work together regardless of who is in Lansing. Then we identify the lawmakers who want to work across the aisle, and we find the organizations that will cheer that work on.

We found a great partnership with our Michigan chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). We’ve been able to collaborate with them in effective ways. Probably the one that we’ve gone the furthest on is civil asset forfeiture and the property rights associated with that policing practice. We’ve co-published several studies with the ACLU and done joint events.

I once walked into a committee room to testify in support of one of the forfeiture bills. The ACLU lobbyist was there, and she said, “Let’s go up and testify together.”

The impact of that shoulder-to-shoulder collaboration was palpable. The chairman of the committee said something like, “Wow, the planets have aligned. We’ve got these two organizations working together.” That collaboration inspired policymakers. That bill went on to pass with bipartisan support.

You have to be intentional about this. Hopefully, you’ve developed relationships with the right individuals and institutions ahead of time so that there’s a basis of trust when you want to work with them.

The collapse of trust of institutions is something that continues to surge. I know media usually has some of the lowest levels. Is that something that the Mackinac Center is constantly thinking about in terms of positioning itself to not only be mindful of but maybe even find ways to capitalize on this new dynamic?

Reitz: Yes. We address it in a couple of ways. Once we identify an issue to prioritize, we think in terms of the real people that we’re going to help. It’s nice if you can have a picture of that person in your mind.

It’s even better if you can say, “This is going to help Mindy or Roger and let’s bring them in and find out how we can work together.” Every study we write, we ask ourselves who we are tangibly helping.

If you walk in our front door, you’ll see three TV screens, filled with pictures of people. They’re not stock photos. Those are photos of actual individuals and families that we’ve helped in some way. Many were clients in important litigation. Others served as heroes for a particular policy issue. Working hard to personalize the issue helps us convey that this organization exists to help people. We don’t just study problems. We fix them.

Another way we address public trust is how we evaluate public policy questions before the Legislature. I first heard this framing from Jack McHugh, who was a senior editor at Mackinac for 20 years. Jack used to ask, “Is this policy going to help people or is it going to help the governing class?”

One of the reasons trust in government has collapsed is that elected leaders are often willing to impose restrictions on the people that they govern, but then elected officials are hostile toward restrictions that are placed on them—things like term limits, balanced budget requirements or open government rules.

Why does so much policy innovation come from the states? I think some people might picture the “Whiz Kids” during the Kennedy administration. They think of these “brilliant” people being at the national level, but all the big policy reforms happen at the states.

Reitz: In one sense, it’s because our Founders designed it to be that way. They wanted to have a federation of states free to experiment with ideas that are not dictated in a top-down fashion. We must give credit to the people who thought about how the country should be constructed under a federalist system.

There’s also the reality that in Washington, DC, there’s so much gridlock that contrasts with state governments. I remember asking one of our college interns a couple years ago: “Can you name one significant good thing that Congress has done in your lifetime?” That person couldn’t.

Then you compare that to a state government where there isn’t as much gridlock, and it isn’t as difficult to get things done. You can accomplish big things.

I’m constantly amazed when you study history and you look at the social movements in America, how often those ideas started in the states. The idea spread to a couple of states and then to a couple more and there’s eventually a tipping point when so many states have tackled an issue that it becomes undeniable at the federal level.

We could name issue after issue where that’s a reality. It’s the way change happens in America.

I like to tell the story of a time I visited Washington, DC, during the Trump administration. We had an idea that we thought Congress should consider. I was there with a handful of other policy experts and advocates, and we spent all day planning to get a subcommittee hearing in the House scheduled.

This was an all-day strategy session just to get the hearing scheduled. I don’t think that meeting ever happened. A lot of time went into planning that idea, and it never came to fruition.

I flew back to Lansing, and a charter school leader called us. They had a problem with the local school district. We thought this was an important issue to address. We introduced her to a few policymakers so she could tell her story. Before the end of the day, a bill was introduced. It passed the Legislature later that session. The speed of action at the local level is significant.

How do we recover a culture of self-government in this nation? It seems like we are constantly fighting centralization, which is sort of the reversion to the norm throughout human history.

Reitz: The administrative state is a huge concern for anyone that loves liberty and wants to see opportunity flourish. I’m encouraged that the Chevron doctrine is being considered now and maybe that will curtail the power of agencies and unelected public servants who don’t have the same accountability that elected members of Congress or state legislatures do. That’s an area for people who are working at the federal level or at the state or local level to pay attention to.

When COVID-19 first emerged and the governor declared an emergency, our director of research, Michael Van Beek, told me, “Someone better read the laws that grant governors emergency power.” So, he did.It was a law that had been there since the mid-1940s and had rarely been utilized.

The governor saw that law, decided to use it, but begin doing things that were outside the scope of her power. Anytime you have something written down in law or statute, it can become a tool for a future politician.

Modesty in lawmaking is important. Lawmakers need to ask, do we need to have a law for this? Is there already a law in the books?

I remember a situation in Michigan a few years back an amateur soccer player punched a referee, who later died. A lawmaker quickly introduced a bill that prohibited assaulting sports referees.

I must give credit to some lawmakers who said this law was not necessary. This was a tragic situation, but it’s already illegal to assault people in Michigan, and adding another law to the books won’t make that more illegal. I think modesty in lawmaking and rulemaking is important and it’s up to us to talk about that as a value.

Tools that allow individuals to keep an eye on their government are important. At a think tank like the Mackinac Center, we rely on public records. We file a lot of records requests and Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests with agencies and local departments.

That’s a tool individual citizens can use as well, whether it’s access to records or meetings. I believe our technological capabilities are about to completely revolutionize the public records regime—the rules that govern access to government transactions and records. It’s only a matter of time before you can enter a request into a bot that then searches all government records and brings you the records you asked for.

There are some exceptions to the disclosure rules, so the public records custodian can review documents and redact exempt information. That too will be automated in the next few years, allowing people to keep an even closer watch on government actions. Those sunshine laws are a component to this process of government accountability.

What does self-governance mean to you?

Reitz: It means a group of people who have gotten together and have agreed upon the process by which they will decide important questions. And, also, what limits the people wish to place on their government. The procedural safeguards are important and we tend to overlook that.

“…what defines self-governance, and then what imbues that with public trust, is public participation, both in the process and in the substance of a question.”

It’s easy to focus on the issue of the day. What did Congress enact? What did the Supreme Court rule on? But what defines self-governance, and then what imbues that with public trust, is public participation, both in the process and in the substance of a question.

Elected leaders have a responsibility to conduct themselves in a way that conveys—even if we end up disagreeing—that they are going to fully engage the stakeholders and the constituents in the process.

What is the next big policy reform that might not be at the forefront of the public’s mind, in Michigan or other states as well? Is there something flying under the radar that excites you or you think you can get traction on?

Reitz: Energy and electricity, particularly in the states. This is one of those modern miracles that we take for granted. When I wake up in the morning and flip the switch, I assume the lights are coming on.

We don’t even think about the benefits of electricity and how abundant it is and how it improves our lives. So much of the conversation on energy policy is pushing us away from reliable and affordable energy sources toward things that may one day make a lot of sense, but the technology isn’t there now.

In Michigan we’re closing coal plants and hoping that they get replaced by solar farms and windmills. The math doesn’t work. We do not have enough electricity generation through those so-called renewable sources to power and stabilize the grid. This is an issue that becomes apparent as brownouts and blackouts happen across the country.

The freeze in Texas a couple of years ago, when a couple hundred people died because of insufficient grid stability, was a wake-up call for some.

Unfortunately, people don’t think about this issue until the lights go off. We are talking to our fellow Michiganders about the dangers of continuing down the path we’re on.

Obviously, there are benefits to energy independence. There are forms of drilling and fuel extraction that are always going to be up for debate. This idea of having affordable, abundant, and reliable electricity is key to our quality of life and our prosperity. The path many states are on right now leads to darkness, cold and poverty.