A judge and priest reflect on American virtue

Below are interviews with former Wisconsin Supreme Court Justice Daniel Kelly and Fr. Roger Landry, a Catholic priest. They both discuss the state of virtue and its importance for the success of free societies. The topic of virtue is a current emphasis in American Habits. The American Founders did not agree on many topics but there was universal agreement that virtue is a requirement for the success and survival of free societies.

In truth, only those that can self-govern themselves can ultimately govern a republic. Does your work in courtrooms encourage or discourage you? What if any insights can you add?

This is an excellent, but exceptionally capacious, question. It might take several doctoral theses to adequately address it, but let me see if I can pare the question down to something manageable for these purposes.

Let’s start with distinguishing between the issues the judiciary addresses, on the one hand, and on the other the systems and procedures for resolving them. I think that’s important in relation to this question because the role of the judiciary, in a very practical sense, is to step in when self-government fails. That is to say, on the substantive level, recourse to the courts becomes necessary when someone causes harm to another, or commits a crime, or is unable to resolve a dispute, etc. Bringing the dispute to the courts engages the compulsive mechanisms of external governance to remedy the failure of self-governance. Therefore, assessing the state of self-governance based on the substance of the disputes presented would yield a uniformly pessimistic conclusion — after all, every case represents, at least to some extent, a failure of that principle.

So although the issues presented to the courts, as a matter of substance, don’t have much to say about self-governance, the way we address them most certainly does. What I have in mind here is the public’s interaction with the judiciary, both in the way it staffs its offices and in what it asks those officers to do. I’ll treat each of those aspects separately.

The impulse to win at all costs is, while understandable, evidence of a failure in self-governance.

On the first aspect, the evidence suggests our level of self-governance calls into question whether we are prepared to responsibly staff the judiciary. Our responsibility (and by “our” I mean here the general public) is to favor the appointment or election of jurists who understand the nature of judicial authority and who exhibit a robust commitment to its requirements. But we can do that only if “we the people” first understand what judges are supposed to do. At both the state and federal levels, government authority is divided between three branches. The division necessarily limits what the officers of each branch may legitimately do — the legislature makes the laws, the executive carries them into effect, and the judiciary resolves disputes according to those laws. The branches are not to poach on another’s authority, nor are they to give away their own. Responsibly selecting someone to serve as a member of the judiciary, therefore, requires an understanding that judges do not make the law, they merely use existing law to resolve the disputes that come before them. A recent survey, however, found that less than half the population can even name the three branches of government. Knowledge of each branch’s role, what it may and may not do, is considerably lower. Self-governance is no easy task under the best of circumstances. But without knowing the standards by which to govern oneself, self-governance is, shall we say, considerably more difficult.

The results of this difficulty show up in the types of jurists we find on the bench. At the federal level, recent appointees to the court have demonstrated a marked interest in returning to the proper role of the judiciary. But at the state level, circumstances are considerably less encouraging as we see judicial activists appointed or elected with some regularity.

The second aspect of our interaction with the courts involves what we ask them to do. That is, what types of arguments do parties and their attorneys make in pursuing victory in the courts? As a Wisconsin Supreme Court justice, I saw a mixed bag. Some parties confined themselves to the law and sought a resolution in keeping with the courts’ authority. But on many occasions, the parties explicitly asked us to rule according to what they believed the law should be, as though we were politicians in the legislature. The impulse to win at all costs is, while understandable, evidence of a failure in self-governance.

How can the law play a role in helping to reform someone who is no longer willing to follow it?

Civilization and the rule of law are a departure from the state of nature, and as such their continued existence requires the ongoing, regular commitment of those in society to be civilized and to choose obedience to the law. In that context, the law plays both a pedagogical and a retributive role.

On the pedagogical side, it informs people that certain types of behavior are so unacceptable that to engage in them is to place themselves outside of society and in a position of hostility to it. The law, however, is entirely inadequate for teaching people how to be virtuous — a role reserved for society’s voluntary institutions. The law’s teaching role is merely to describe the behavior that will subject citizens to the coercive attention of the state. And that brings me to the law’s second role.

The law has the power to encourage people to return to the minimum acceptable civilizational standards through the judicious application of rehabilitation and punishment. But these external inputs can only indirectly encourage a person’s reformation, they cannot directly accomplish it. Ultimately, as an independent moral agent, it is up to each person to choose civilization and the rule of law. Punishment and rehabilitation can make that option the wiser choice, but it cannot force it.

What do you see as the consequence for communities when people don’t have the habits of virtue—perhaps even how it ripples through to decay virtue in others?

There is a sentiment, I’m not sure how broadly shared (although it is certainly not uncommon), that so long as a behavior is not illegal, polite society must affirm its acceptability. This misunderstands the role of the law as well as the nature and necessity of virtue.

The law sets a minimum civilizational standard for those who wish to be part of our society. Virtue, on the other hand, describes behavior that is capable of producing human flourishing. Conflating the two would have disastrous consequences. Lowering virtuous expectations to the level of the law would result in a coarse, cold, callous world in which no right-minded person would wish to live. Raising legal expectations to the level of virtue, on the other hand, would destroy the freedom that is necessary for virtue to thrive. And, inasmuch as virtue quite often flows from religious convictions, it would also insert the government into a realm where it has no jurisdiction.

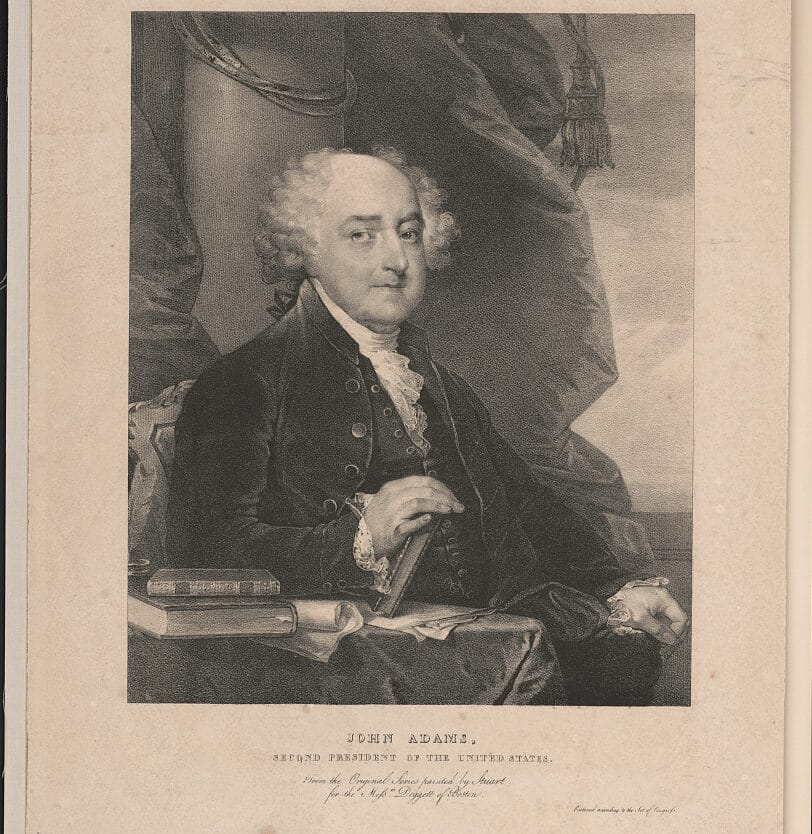

John Adams recognized the importance of maintaining the separateness of these standards when he observed that “our constitution was made only for a moral and religious people. It is wholly inadequate to the government of any other.” He knew the compulsive, blunt apparatus of government could not rightfully make people be what they ought to be. But he also knew that if the people lack virtue, society (and the government it serves) would not survive.

How and in what ways does a good judge in our legal system exercise virtue?

The chief virtue of a jurist is humility. This is not a role for the ambitious, the self-important, the enterprising. A jurist’s responsibility is not to decide what he thinks is “right” according to his own standards (or what he thinks society’s standards might be) or to pontificate on what the law ought to be. It is, instead, to humbly accept the law from its authors (either the legislature or “we the people”) and use that law to impartially resolve the case before him.

In our constitutional form of government, the identity of the jurist is, ideally, entirely irrelevant. In any given jurisdiction, the law is the same regardless of who might be presiding over a case. And so, ideally, the identity of the jurist would have no impact at all on how the case is resolved.

This is one of the reasons jurists wear black robes. The unadorned robe, identical to the robes worn by all other jurists, symbolizes the uniformity of the law that is the sine qua non of justice. This is, of course, an aspirational standard — human fallibility will sometimes produce varying results even when all involved are doing their best to objectively apply the law. But pursuing that standard requires the virtue of humility: The conscious subordination of one’s own thoughts on what the law ought to be in favor of the law its authors actually created.

Daniel Kelly is former judge who served as a Wisconsin Supreme Court Justice (2016-2020).

In truth, only those that can self-govern themselves can ultimately govern a republic. Does your work in ministry encourage or discourage you? What if any insights can you add?

With regard to self-governance, I can’t respond better than echoing the words of Pope Benedict XVI at the White House in 2008.

“Freedom,” he appreciatively stated, “is not only a gift but a summons to personal responsibility,” which calls for “the cultivation of virtue, self-discipline, sacrifice for the common good and a sense of responsibility to the less fortunate.”

He concluded, “Freedom is ever new. It is a challenge held out to each generation and it must be constantly won over for the cause of good.”

In my work as Catholic Chaplain at Columbia University, I see both promising and worrisome signs. There are many students, Catholic and otherwise, who are striving to be virtuous, self-disciplined and self-giving.

But the dominant strains of our culture, present on campus, are forming the majority in a self-centered, relativistic, hypersensitive, immature, sentimental hedonism, which is totally inadequate for self-governance not to mention true leadership of others.

To lead, one needs courage, but the dominant culture is forming people toward victimhood, cowardly “safe spaces” and grievance.

To lead, one needs wisdom, and our culture is failing to transmit the wisdom of the centuries because of an ideological rejection of western civilization in favor of various forms of social Marxism, epistemological deconstructionism and fads.

To lead, one needs strong families that train people in virtue, and the dominant culture has been long trying to undermine the family as it tries to bring the sexual revolution and its separation of love, marriage, sex and children to its ultimate conclusions. Once we lost the meaning of sex as a verb, we lost it as a noun, and that’s led with gender ideology to undermining even basic human anthropology and our capacity to state the truth.

To lead, as Pope Benedict mentioned, we need a proper understanding and exercise of freedom, but the dominant culture looks at freedom as untethered from truth and responsibility, as the capacity to do whatever one wants. As we’ve been seeing, this is a recipe to endless social strife not to mention to might makes right, as the freedom of the powerful will trample the freedom of the poor and vulnerable.

These trends, and others, are very worrisome, but it’s not inevitable that they will triumph. Everything depends on the active, not passive, courageous response of those who are the grateful heirs of the virtues and values of those who helped build this country, including many new immigrants, as well as on whether we have and educate children who will be capable to accomplish what Benedict described.

What do you see as some of the most troubling consequences for communities when people don’t have the habits of virtue—perhaps even how it ripples through to decay virtue in others?

Virtues are good habits, acquired through repeatedly doing good actions. Our communities need those good actions and, even more, the good people of solid character formed by those actions. We need honest, just, prudent, generous, hard-working, courageous, patient, responsible, magnanimous, loyal, loving people who know how successfully to control their addictions and vices, like anger, pride, greed, jealousy, laziness, disloyalty and hatred.

There’s a Polish aphorism that the amount of police officers you need is inversely proportional to the people who can police themselves. That’s basically saying without virtuous people, without those intrinsically motivated to do good, we descend gradually into a situation in which we need more cops and courts to help dissuade others extrinsically not to do evil out of fear of the consequences.

There’s a Polish aphorism that the amount of police officers you need is inversely proportional to the people who can police themselves.

That’s essentially the troubling consequence President John Adams foresaw when he declared, “Our Constitution was made only for a moral and religious people. It is wholly inadequate to the government of any other.” He was prophetically emphasizing the importance of virtue for the enduring survival of our experiment in ordered liberty.

What ways can we develop virtue if we don’t feel very virtuous or maybe not sure what it even means?

Virtues are acquired through repeated good actions. The more we tell the truth, especially when it would be convenient to lie, the more truthful and honest we become. The more we take responsibility for things before we’re asked, the more responsible we become. Virtues are the fruit and seed of good acts, making doing the right thing gradually easier and almost second nature.

Education plays a major role in the formation of virtue. We need to teach the virtues — in schools, homes, Churches, communities, and culture — at a time in which “values” are being taught instead. We also need to help the young ask the bigger questions about what type of person they want to become.

St. Gregory of Nyssa, a fourth century Doctor of the Church, once stated, “We are in a certain way our own parents, creating ourselves as we will by our decisions.” We help form our character by the choices we make, by the habits we cultivate.

Example is also key. People are more persuaded by witnesses than manuals. We need to see that it’s possible and joyful to live virtuously. That’s why it’s so important for us to set good example for the young.

What do you think a good citizen in a highly pluralistic republic looks like?

I think a good citizen is someone with a proper love for our country, a healthy patriotism, one who lives by the principal articulated by President John F. Kennedy at his inaugural address, “Ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country.”

The good citizen uses his or her freedom to give more than get, to serve rather than be served, to take initiative rather than wait to be asked someone else to step forward, to volunteer a lot.

The good citizen works hard at school and then on the job. He or she keeps commitments, especially to his or her spouse, children and parents.

The good citizen pays attention to what’s happening in the neighborhood, city or town, state and nation and more than complaining about problems, takes responsibility to try to address some.

The good citizen votes wisely and, when others aren’t doing the job, gets involved as part of the political process, assisting good candidates or even considering running for office.

The good citizen knows the history of the country, is familiar with its founding documents and traditions, and has a love for the country that’s solid and infectious.

The good citizens respects those who differ, seeks to handle disagreements amicably, without thinking every opinion is of equal value, or sitting out when dangerous ideas start to metastasize.

The good citizen seeks to build up not just himself or herself, but his family and community.

The good citizen fights for his country’s good, considers serving the country in the military and honors those who do.

To use Biblical images, a good citizen is salt, light and leaven.

Father Roger J. Landry, a priest of the Diocese of Fall River, Massachusetts, serves as Catholic Chaplain to Columbia University in New York City and to the Thomas Merton Institute for Catholic Life.