The freedom conservatives can’t ignore

All throughout the year, but especially during the late spring/early summer when the U.S. Supreme Court releases its major decisions, the media buzzes with headlines about religious liberty.

Opponents of religious liberty cast its advocates as pro-discrimination or covert Christian nationalists. Supporters often point to John Adams notable assertion that our “constitution was made only for a moral and religious people. It is wholly inadequate to the government of any other,” and insist that religious liberty is a necessity for a flourishing American society.

But beyond the generalizations, what do we mean when we talk about a legal victory for religious liberty? And why should conservatives care? There are several different ways that the freedom to practice one’s religion manifests in the courts.

At times, the judiciary’s authority to interpret the law is truly needed to clarify the meaning of the First Amendment’s Religion Clauses. Think of the dispute over whether or not St. Isidore’s virtual Catholic school could obtain charter school status and state funding without violating the Establishment Clause. While the decision of a religious institution to pursue a financial relationship with the government requires careful prudential discernment, the question of whether such church-state partnerships are constitutional is a constitutional question. In the St. Isidore case, the Supreme Court ultimately split 4-4 after Justice Amy Coney Barrett recused herself, leaving in place the previous ruling that found a religious charter school unconstitutional. Because of the even split, no precedent was set. Court watchers can expect a similar case to reach the Supreme Court before long. This is an example of a religious liberty court case that is necessary to decide a constitutional question, shaping the scope of religious rights in a way that local governments and legislation cannot.

At other times, judges aren’t answering religion or religious liberty questions directly, but are only making space for conservative states to enact sane policy. For example, this year in Planned Parenthood v. Medina, the Supreme Court ruled that states can withhold government funding from abortion providers. Without the Court intervening, fiscal and social conservatives would be unable to implement policies that prevent money from flowing to abortion providers. Cases like Medina are necessary, not to expand or clarify First Amendment rights, but to allow states to enact conservative policies without excessive federal interference.

Finally, sometimes litigation is often an unfortunate necessity that could have been avoided if states did not pass bad laws. The Wisconsin Catholic Charities case, decided unanimously during the Supreme Court’s most recent term, reversed a Wisconsin court’s ruling that the Catholic nonprofit was not legally a primarily religious organization. Wisconsin law provides exemptions from unemployment tax for organizations “operated primarily for religious purposes.” The Wisconsin Supreme Court ruled that, since Catholic Charities serves members of all faiths and does not proselytize the people it serves, its activities could be accomplished by a secular organization; somehow the court concluded that these circumstances make an organization not primarily religious. Because of this, Catholic Charities initially failed Wisconsin’s “religious purposes” test. The U.S. Supreme Court had to step in and correct the error, clarifying that making such arbitrary distinctions based on a religious organization’s religious beliefs and practices violates the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment. Again, such religious liberty court cases are quite avoidable if states didn’t make bad decisions in the first place.

So back to the original question: why should conservatives care about religious liberty in the courts?

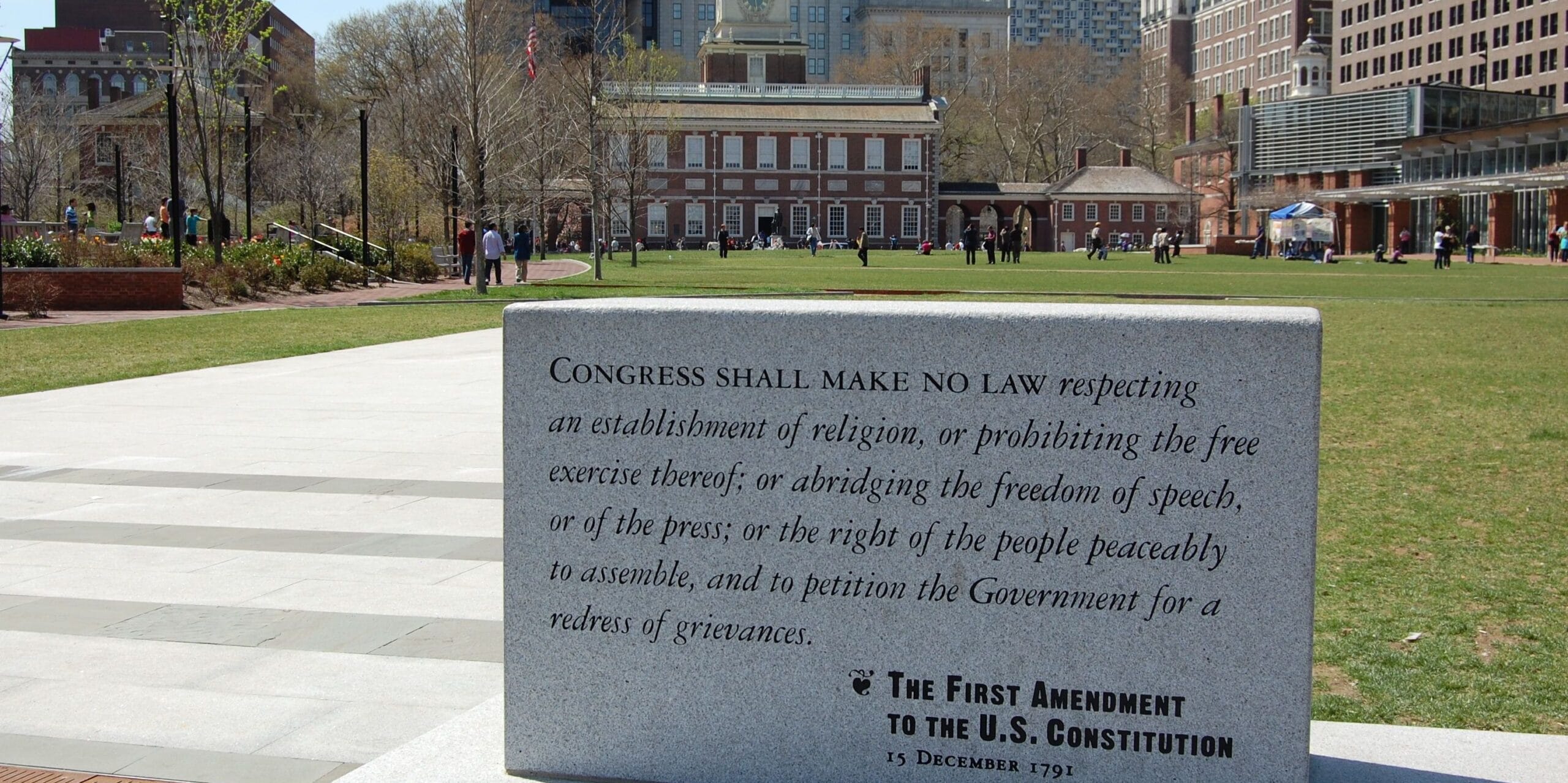

First, we care about the U.S. Constitution. For almost a century, progressive trends have attempted to limit the free exercise of religion to the freedom of private worship. But religious liberty was understood at the time of the American founding to mean the ability to exercise — that is, to publicly live and act on — one’s religious faith, not merely to worship at home or in church. Conservatives should care about properly protecting the very first freedom named in the Bill of Rights.

Second, robust public exercise of religion strengthens civil society. It keeps big government from usurping the roles of caring for the poor (such as feeding the hungry and housing the homeless) and educating children that can be better and more properly accomplished by religious individuals and organizations. “Nondiscrimination” laws that push religious institutions out of the public square because of their beliefs and hiring practices, burdensome tax and regulatory regimes, etc. make it extremely difficult for religious organizations to function in accordance with their faith. As a result, government steps in, grows accordingly, and takes an increasingly large role in society that properly belongs to private (and often religious) institutions.

Solving this problem of government interference that prevents religion from fulfilling its public role often does not need to involve the federal courts. States have a role in proactively solving these problems on the local level, thus allowing religion to flourish. A few brief examples will help illustrate the kinds of laws state legislatures can enact to support faith-based individuals and organizations.

Nondiscrimination laws at the state level often make it unlawful for religious organizations to make decisions based on religion, sex, sexual orientation, and gender identity. These restrictions can make it impossible for religious organizations to function in accordance with their religious principles and practices. Proper exemptions from such laws, especially regarding hiring practices, prevent religious organizations from having to go to court in order to hire employees who believe and practice the same faith.

Religious organizations are generally nonprofit entities, which means they operate to accomplish a religious, educational, and/or charitable mission. Yet many tax codes treat them the same way they treat for-profit entities. Broad tax exemptions for faith-based nonprofit organizations prevent dollars that were donated, not earned through for-profit endeavors, from being taxed so that religious organizations can spend every dollar accomplishing their missions.

Many states heavily regulate religious organizations, forcing them to file business registrations, charitable solicitation registrations, annual renewals and reports, etc. Limiting regulatory red tape (such as complicated state registration forms and audit requirements) allows religious organizations to focus on their work rather than on government bureaucratic requirements.

Some states have taken active steps to protect faith-based organizations. Others impose heavy burdens, such as regulatory requirements and restrictions against religious exercise. Napa Legal’s Faith and Freedom Index analyzes and grades each state on the legal environment it creates for religious nonprofit organizations. The Index gives motivated state leaders a tool to identify areas of improvement and reveals the kinds of laws that can help or hinder the flourishing of Americans across the country.

Religious liberty is good for society. It allows religious individuals and organizations to live their faith in the public square and work to advance the common good without unnecessary interference from big government. Advocates of religious liberty rarely ask the government to intervene on behalf of religion. Rather, we are just asking the government to get out of the way so religion can flourish and strengthen our society.

Joseph Clement is content and program manager at Napa Legal. Frank DeVito is senior counsel and director of content at Napa Legal.