A look inside the coffin

December 12, 1799

The day was bitterly wet and cold, making riding difficult.

Despite this, dispatches from the Capitol arrived early, pre-empting my morning inspection and keeping me pouring over maps and letters throughout the day.

In the evening, Jefferson himself arrived with grave news – the French general, Napoleon, has landed upon Louisiana with threatening force.

And he returned my sword – a gift from President Adams who calls for me once more to leave my seat beneath my own Vine & Fig tree.

GW

____________________

AS the great ones have little time to record even a fraction of the matters to which they attend, it is left to us little ones to write of those whose actions ripple through history.

And so, dear reader, you must forgive me if I write poorly or focus on what matters little. Had I literary art I would have doubtlessly begun this chapter with a quote from Herodotus or the upstart Goethe, but, risking exposure to my obvious lack, I start with a simple entry from a diary that was never written to be read.

Perhaps the wheels of fate would have turned differently, and the day meant to slip into quiet oblivion, but fortuna forever twists and turns the paths of men. Despite that our old father, Washington, has earned and deserved his rest, our world was fated not to grant it. Perhaps it is to be his in another.

The southern swamps of our rough frontier land have slowed Napoleon, and our General has kept our army intact. Now the French people tire of war.

Battle in our American backwoods has been bloody, but both generals are still standing. And so this morning, in a ruined church on the edge of Augusta, Georgia, they met to discuss terms for peace.

And I, the simple scribe, here record this meeting as best as am able.

_____________________

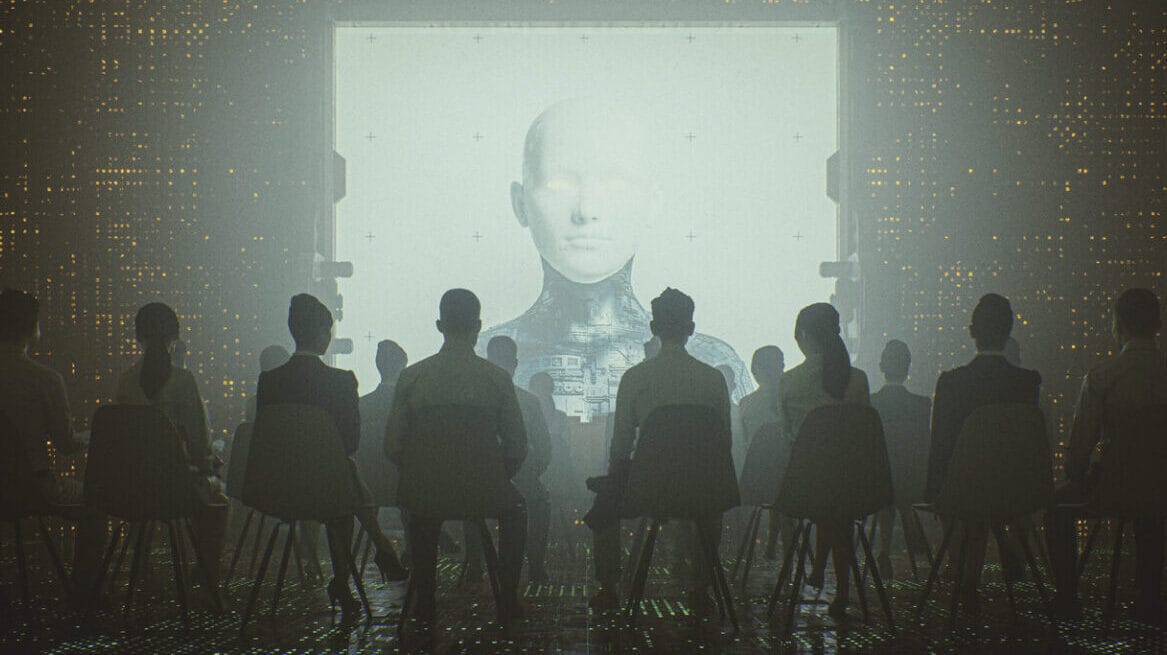

Washington arrives first to the church. His aides stand watch outside and he enters the church alone. Old he seems – a man accustomed to much care and worry. His shoulders stand tall, but his head is bent.

Good builders took care and pride when erecting this stout place of worship. If not for the war, I suspect it would have lasted centuries. Even now, the walls of stone still stand strong despite the shelling, but the pews are reduced to mangled planks of wood. In the corner are remains of an old altar.

Our General walks to the front of the church slowly. In the center of the nave he comes upon the remains of a small coffin – the size of a child perhaps a few years old. This gives him pause. No words are said, but the flutter of his lips bely the fact that he is praying. His repose is not to last long.

“Well, General?” Napoleon calls out from the church narthex. The young general uses English with a heavy accent – not French to my ear – before switching to French. I serve to translate for both. “I’ve long looked forward to this meeting.”

Washington looks to Napoleon with a frown but speaks respectfully, “You have spent much blood to arrange it.”

“We have much to spare. Nothing great is arranged without rivers of it.” The young man is nervous. He seems eager to make Washington understand, and looks up to him almost with longing, “You have seen this, surely.”

Our General looks to the coffin, “We are not so free in spending.”

“These are hardly the words of a revolutionary — let alone the best the world had ever seen.”

Washington smiles at this. Napoleon notices.

The young general nods, “You smile. You do not consider yourself a revolutionary, perhaps?”

“Forgive my mirth, sir.” Our General speaks sincerely, “I could not help but notice the slip from present to past tense. Doubtless a matter of translation. It matters not.”

I, the translator, thus stand shamed, but the blood rising in my cheeks is suddenly abated when, for a brief moment, I think my General Washington is winking at me. I cannot help but smile, though a murderous glance from the great Bonaparte quickly chills my humor.

Washington commands his attention in an instant, “You ought be commended, General Bonaparte. Your prowess in a land unknown to you, our dear America, far outstrips any British general that commanded here. In first battle with you, I learned more mathematics than in my entire previous life. And you pay me a great honor when speaking of your wish to meet with me. I cannot help but wonder why.”

Napoleon looks upon Washington with a piercing yet longing glance. Then, almost with reluctance, “I wanted to meet the man whose homeland loved him.”

He fidgets with his sword while Washington considers this.

“Am I so loved that you pay such a price?”

“Perhaps.”

“You spoke of blood. You realize that we will never surrender, never sue for peace until the last drop of ours is spilled or until you have left America entirely?”

“Do you dream that I wish to remain? There is more beauty in a single village in silly France than in your entire continent.”

“And yet, you are here, General Bonaparte.”

Napoleon grips the handle of his sword now in a tight fist. “So I am,” he says.

“Perhaps you dream of an American Empire from where you might rule the world?”

“It is not even for you, father Washington, to presume upon my dreams.”

For the first time I notice that Washington, too, has his hand on his sword. They both face each other as if ready to go to blows.

At last Napoleon speaks, “My men follow me around the world. They live and die at my word. Well I know, France would not – even less my own Corsica. You say that the entire blood of America would empty for you, and, truly, I believe you.”

The young man comes close to our General now. Bonaparte’s hand has dropped its sword. Instead, his arms reach out almost as if in an embrace.

“How is it, General Washington, that they will all die for you?”

“It is not for me.”

Napoleon pulls back at this. “What then? Democracy? Freedom?” He spits. “Men cannot understand, much less die for these things. Do not speak of them to me.”

Washington sees that the young man is in pain. “My son, I do not understand you. I am not a revolutionary. I am a farmer. And yet, I keep my land and wish to dwell on it. In that, I speak for my Americans. It is perhaps our original sin, this American habit – that we would not be ruled.”

“Perhaps you overestimate your children. A whiff of grapeshot would change even an American’s mind. Even without that, they called to make you their king – how is it, father General, that you do not dream of an American Empire from which to rule the world? The goddess of fortune smiles upon you and you scorn her to return to a simple farm. Do you not dream of spreading liberty throughout the world, casting off the shackles of the old world to free men of every race?”

Washington looks down to the coffin before he speaks, “You presume upon my dreams accurately. I do not dream of making all men free so that they might serve me.”

Napoleon answers, “All men serve. The free man chooses his master.”

Our general nods, “And may it be a worthy one.”

“Ah so that is the secret—you consider yourself unworthy? Unworthy of keeping the flame of freedom alive.”

“My time is nearly over. If I am needed to keep the flame alive, then it will perish.”

“And yet you fight me. You bear arms better than any Italian prince or German general.”

Washington holds out his hands, “I am old and grow tired, son. The time has come to speak plainly. I speak for myself and for every American – we desire to go home but never will so long as you bear arms in our lands or on our borders. Now it is your turn. Why did you call for this meeting?”

Napoleon waits as if listening. For a moment, we can hear the sounds of cicadas outside.

Then, the man from Corsica speaks, “Insight. I come with insight. Mark my words, father General, at the end of every rebellion is a savior. Your American one is not different from any other. It might take two decades or two centuries, but America’s savior will come. It might not be you nor me, but there will come a time when your children will kneel to a master that might save them.”

The lines of care are etched in Washington’s face. “You have studied our terrain well, my son. I pray that you have not studied our hearts as accurately. Return to France and offer this message to those that might hear it there. We will not.”

“Perhaps I will. Earlier you spoke of blood. There is one thing far more precious than that—time. I have wasted much time with you and with America. I cannot dream that this land will ever be worth a fraction of it.”

He turns to stride out of the church. Washington calls out to him. “Will you leave America, Bonaparte?”

Napoleon does not stop, but he does reply, “Perhaps I shall return to Europe—it would be a worthy place to rule. Or perhaps I will prostrate proud Washington to the ground. Who can tell?”

With that, the parley is over and the French general is gone. The sounds of hooves slowly fade away.

Washington looks down at the coffin and murmurs, “Strange that a man so magnificent is afflicted with the smallest of dreams.”

He reaches down and cracks open the child’s coffin, peering in for an instant, but then suddenly straightens and makes his way out of the church as well.

I tarry so that I too might look. Sunlight streaming from the windows illuminates clearly—the coffin stands empty. Our General is impatient, and so I hurry away as well.

James Pinedo is marketing manager at State Policy Network.