The managerial state and the fate of religious liberty

What if the context from which the language and concepts of religious liberty emerged no longer exists?

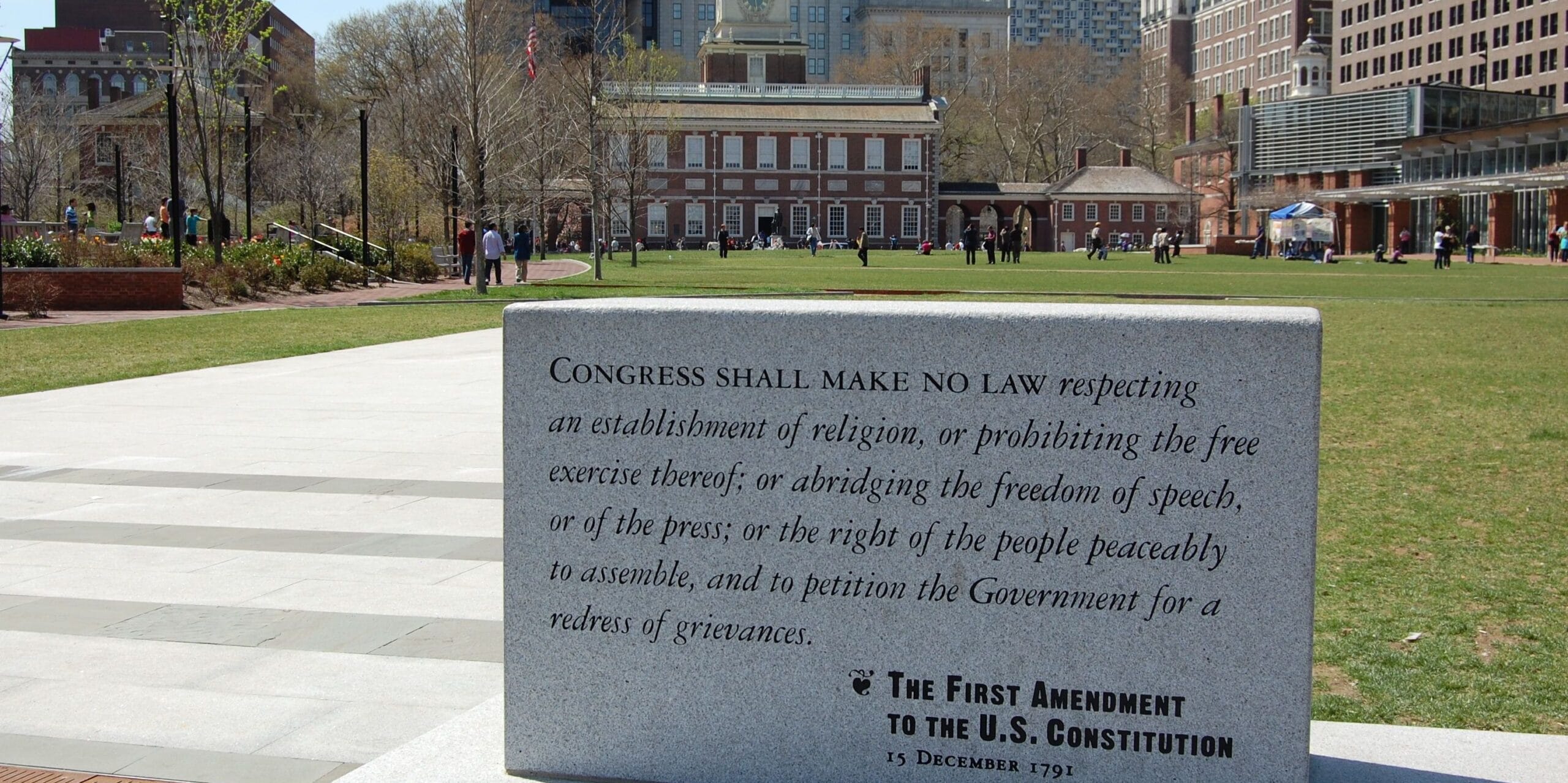

If individual liberty, natural rights, freedom of worship, freedom of association, and later the separation of church and state and pluralism are the vocabulary of religious liberty, we could roughly identify them with the Protestant and capitalist societies with representative democracies where they first arose.

What if a new form of social and political organization has overtaken that context? Does the vocabulary of religious liberty remain intelligible against the current grammar of power and social organization?

While not focusing specifically on religion or religious freedom, James Burnham argued in “The Managerial Revolution” (1941) that capitalist society—of which representative democracies and constitutional republics were the handmaidens, and which we can identify as a coherent context for religious liberty—had already all but disappeared.

Burnham’s legacy has been more or less stripped for parts, but he offers a potent description of what lay ahead.

Before the rise of the capitalists, power consisted in the scepter and the crosier, often held by the same or similar hands. Lords, kings, and the Church raised crops and armies from the lands they controlled or from tithes and taxes. But new means of prosecuting wars, making and trading goods, and generating revenues required ships and steel and industrial capital and new financial instruments. A new locus of power, in capital and amongst the capitalists, arose from the needs of the feudalists, and did so almost without fanfare.

With the rise of capitalism’s free wage earning, individual rights to property and productive means, and natural rights, came also the categories of religious liberty. Religious liberty’s resort to the same or similar categories of the individual, freedom of worship, and later the separation of church and state and pluralism have been the concomitants of parliamentary governments representing the interests of capitalism and fundamentally capitalist social arrangements. With the rise of capitalist social relationships, religious declarations either advanced or adapted to the decline of the monarchs and feudal lords and the rise of the capitalists. A framework of religious liberty helped instill confidence in the social order.

The sunsetting of the feudalists and monarchies by the capitalists and the rise of capitalist states either gave rise to, or were abetted by new religious declarations affirming the rights of the individual, the freedom of his conscience, and the independence of his church from feudal spheres of power. In other words, the age made a capitalist out of every former subject, whether he owned a factory or worked in one, or whether he still held on to fragments of remaining feudal titles or institutions — and affirmed and asserted his religious liberty wherever he went.

Roger Williams’ eventual invocation of the separation of church and state in this outlook made formal in the sphere of religion and politics what was already in process when it came to generating revenue and warmaking. The capitalists had fully overcome the feudalists.

Where, though, are the capitalists today, asked Burnham in 1941? He argued that insofar as the capitalists overcame the feudalists, the capitalists had already passed away amidst the rise of the increasingly complex technological societies of the early 20th century. It was not socialism that had taken its place, but rather another arrangement of power and social relationships, and with another ruling class entirely.

The scope of federal monies and the ramifications of sweeping managerial state policies swamp cities and states.

The capitalists, he saw, may nominally have owned productive means, but spent their time in philanthropic endeavors or enjoying vacations. They had little control over their operations. Instead, the complexity and elaboration of the new, more advanced industrial societies had given rise to a new ruling class, that is, of managers, who controlled productive means and operations.

And that class of managers, whether employed by the state or by private enterprise, was the same kind of person whether businessman, scientist, engineer, or bureaucrat. Their coordination with the state, increasingly also administered by managers, was hand-in-glove. Regulatory apparatuses, industrial policies, and trade relations could, to varying degrees, preserve or limit what appeared to be free enterprise, but on either side of the state, the process remained in the hands of the managers.

Managerial society, Burnham saw, was too complex or technical for diffuse individuals, even powerful capitalists, to direct, or for their representatives in congresses and parliaments, which he thought would amount to little in the new society.

Indeed today, we could compare the efforts elected representatives exert on lawmaking with their delegation of authority to regulatory agencies and experts, that is, to a class of managers, who function as policymakers. We could also note a steady personnel exchange between private enterprise and state and regulatory agencies, as well as states’ steady hand in building “robust public-private partnerships” and making “strategic investments” with private businesses.

Here is the backdrop of the managerial society against which thinking about religious liberty can occur anew. The new context is a deep integration of the state with private capital and enterprise under the auspices of the managerial state, a new ruling class of managers, and their prevailing ideologies. The context from which the categories of religious liberty emerged has changed.

So what have religious bodies done with their religious freedom in this new context? It is today the religious bodies that have seen which way the wind is blowing that have cozied to, coordinated with, or rejected the managerial state. Whether the decision to coordinate is wise, from the standpoint of the integrity of those religious bodies or the coherence of their religious teachings, is a matter for the theologians, but it is at least lucrative in the present social structures. Meanwhile, other religious-adjacent organizations adverse to parlaying with the state have charted successful courses avoiding it.

It matters little for discussing religious liberty, whether integrations by religious bodies can be characterized cynically or not, for example, by “following the money” or seeing “who goes to dinner with whom.” What they indicate are changing social structures and a new kind of state.

With President George W. Bush’s Faith-Based Initiatives program, which allowed religious groups to receive federal funds, an ostensible victory was won for equal access to federal funding for religious bodies. Although overt or implied coordination between the state and religious bodies had occurred beforehand, by 2004 about 10% of all federal grants went to religious organizations. At the time, the administration said religious groups were well-suited to address local and community needs.

Nearly 25 years later, the engagement of religious groups with the United States’ predominant political issue — immigration — reveals religious groups coordinating with the federal government to enact executive branch policy objectives. That coordination represents a new species in the genus of “public-private partnerships.” Its nationally transformative scope, carried out locally, illustrates a new grain of power.

Among those groups serving as executive branch proxies in facilitating the Biden Administration’s immigration objectives, Catholic Charities USA was one of the foremost recipients of DHS grants for the resettlement of migrants in the United States. The organization collected more than $2 billion between 2020 and 2024. Catholic Charities’ member agencies saw parabolic growth in revenues under the contracts. The Fort Worth chapter saw its revenues multiply by 34, and the Houston chapter alone took in grants exceeding $500 million.

Other groups, such as Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Services and HIAS, too, operated as executive branch proxies in migrant resettlement, receiving awards in the hundreds of millions. DHS Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas served on the HIAS board before his appointment by President Biden.

Whether spheres such as the church or the realm of private faith or the state ought to remain separate or have been compromised by one another in this relationship is secondary to understanding the relationship itself and its implications.

One consideration is the flattening of subsidiarity and federalism through the coordinating efforts among formerly discrete spheres by the managerial classes. The scope of federal monies and the ramifications of sweeping managerial state policies swamp cities and states. In 2022, federal funds accounted for 36.4% of state budgets.

In the case of immigration, NGOs and faith bodies reified sweeping executive branch policy directly in local communities. Whether one agrees with the policy or not, the relationship is clear: private citizens are more or less bypassed in the process. To whom can they go? When state and local government managers, private business managers, and private entities such as religious organizations coordinate with federal managers, the managerial state operates more or less totally.

With a changing of the guard under the second Trump administration, grants for migrant resettlement virtually ceased. However, other DHS grants are now available to religious bodies and non-profits deemed at risk of terrorism, funding both physical and cybersecurity measures. Organizations receiving the funding must, however, cooperate with immigration enforcement when called upon and dispense with ‘DEI’ programming.

Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-CT) protested the requirements, but who inhabits the Oval Office and the will of managers to implement policy will carry the day. The relative coordination of managers, and in this case religious bodies, remains beyond representatives’ control.

Likewise, President Trump’s reforms might transform the actions of the state, be thwarted by a managerial apparatus, or his successor may consolidate or roll back that transformation, but so far it appears the reach of the state and its coordination with private entities in directing the new type of society remains intact.

Thinking of religious liberty might then recognize the centralization of power in the executive branch and emphasize who manages the totality of the state: in other words, personnel is policy. Recognizing the perhaps greater, albeit distributed, power of the ruling class of managers stresses religious bodies’ engagement with managerial structures, and particularly, the ideologies of the managerial class. Can the traditional conceptions of rights and duties and the public square, and the carve-outs and habitable niches for religious bodies, withstand them? In any case, a new context in which to conceive of religious liberty has emerged.

John Zambenini’s writing has appeared in The Living Church, The Midwesterner, Ohio.news, and Drudge Report. He lives in North Carolina.