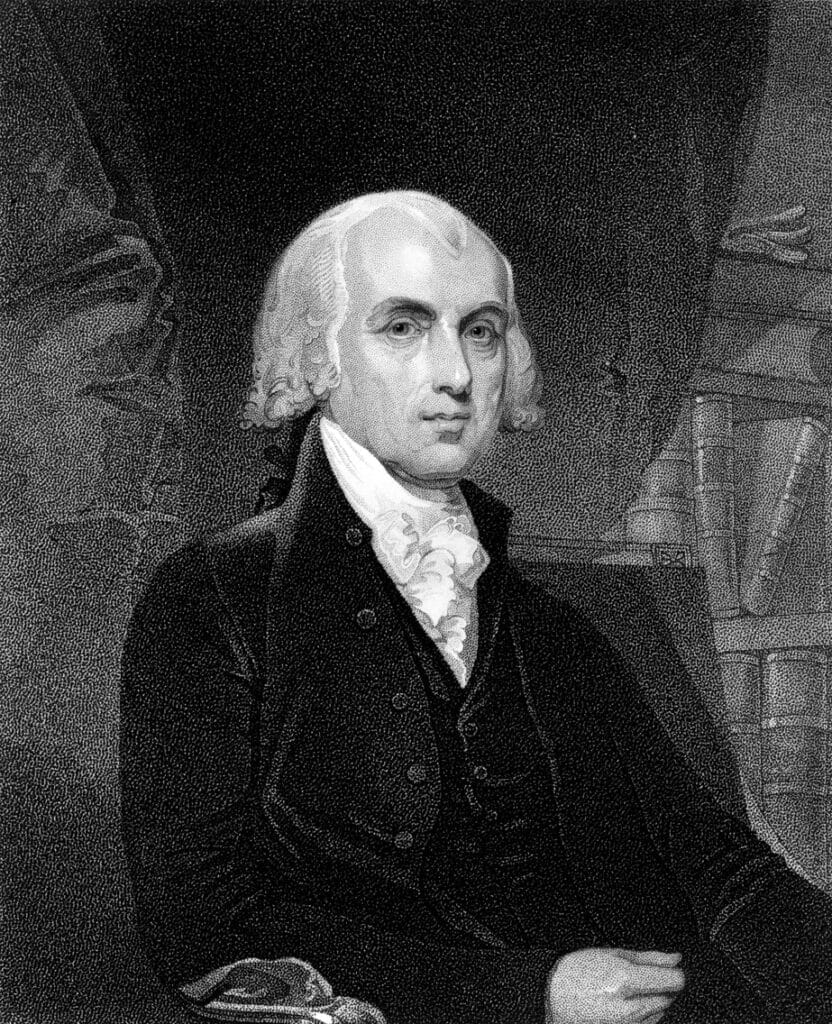

Madison’s blow to ‘religious toleration’

James Madison’s devotion to religious liberty was not merely a political position but a philosophical breakthrough that elevated America’s understanding of rights.

When Virginia’s Declaration of Rights was drafted in June 1776, a young Madison objected to George Mason’s use of the word “toleration” to offer space for religious minorities. Toleration, he argued, implied a permission granted by authorities, something that could just as easily be withdrawn. Reflecting the influence he would later have over the Bill of Rights, Madison prepared an amendment stating “All men are equally entitled to the full and free exercise” of religion.

As Richard Brookhiser observes in his brilliant biography of our fourth president, “Madison’s language shifted the ground of religious liberty from a tolerant society or state, to human nature, and lifted the Declaration of Rights from an event in Virginia history to a landmark of world intellectual history.” The “toleration” sentiment pushed by Mason and others reflected John Locke’s writings on religious accommodation, but Madison reframed liberty of conscience as a natural right rather than a favor to be dispensed by the state.

This early stand in Virginia would shape Madison’s lifelong commitment to protecting freedom of conscience and few understood better than Madison that a full allowance of religious liberty was essential for securing all political freedoms.

His “Memorial and Remonstrance against Religious Assessments” (1785) would later become a defining text in the American tradition, blending theological, philosophical, and political arguments to oppose state-sponsored religion. A big part of Madison’s reasoning was simple: He favored a free market of ideas when it came to American religiosity. Competition in the marketplace, he believed, would foster religious flourishing and growth. This proved especially true during the expansion of the colonies westward, as denominations and Christian traditions aggressively competed for attendees and church members.

He believed that a state subsidized religion, favoring one tradition over another, not only promoted persecution, but also hollowed out the core of true conversion and belief.

“The Religion then of every man must be left to the conviction and conscience of every man; and it is the right of every man to exercise it as these may dictate,” wrote Madison.

Madison’s lifelong commitment to religious liberty was shaped by early influences, particularly witnessing the growing number of Baptists persecuted by his own Anglican tradition in colonial Virginia. Just a few years before his work on the Virginia Declaration of Rights, seeing Baptist ministers imprisoned merely for preaching, emboldened his quest against a state-sanctioned religion. “So I leave you to pity me and pray for Liberty and Conscience to revive among us,” Madison wrote to a friend after the experience.

Another major influence on Madison was his education at Princeton, where he studied under the Presbyterian minister and future Declaration of Independence signer, John Witherspoon, whose teaching deepened Madison’s grounding in moral philosophy and republican thought. Witherspoon was heavily influenced by the Scottish Enlightenment, which sought harmony between faith and reason and stressed the importance of religion for sustaining a virtuous society.

While Madison was baptized Anglican and regularly attended worship services, he gravitated toward a strong preference for the Presbyterian form of church government, which was less hierarchical and more representative. “This was a welcome alternative for Madison, who did not care for the aristocratic undertones of Anglicanism,” wrote Jay Cost in his biography of Madison.

Reformed Protestantism particularly stressed the theological concept of “The priesthood of all believers,” which played a substantial role in awakening much of Western Europe and particularly the newer American colonies to the concepts of representative government, given that the governance of the church was no longer merely the role of the clergy but entrusted to the laity. Madison was undoubtedly influenced by these ideas under Witherspoon’s teaching.

As Father of the Constitution, Madison understood that the religious persecution and sectarian strife of the Old World were warnings for the New. His solution was to limit government’s power over conscience and guard against the tyranny of majorities that might impose their will on dissenters. Just as the Constitution must continually be upheld to preserve ordered liberty, Madison’s rigorous defense of religious freedom reminds us that a healthy republic depends not only on the protection of rights but also on the cultivation of virtue among its citizens.

Ray Nothstine is editor of American Habits.